Existential thirst begins from the very first moments of life, when human beings enter the world with needs that go far beyond food and shelter. Among these is the need to tell stories—to make sense of one’s own experiences and those of others. This need is not one the body can satisfy. When a baby cries, it is not only hunger or fatigue that calls out; it is a plea to be understood, to be heard, to have one’s existence acknowledged. Throughout life, this existential thirst for narrative stays with us, taking many forms: conversations with others, writing in a journal, reading stories, or experiencing art and music.

The Roots of Existential Thirst

At its simplest, storytelling is a way to create meaning out of suffering and the complex fabric of living. Each person, when faced with pain, frustration, or loss, becomes “thirsty” in some sense—thirsty to understand, to speak, to be heard. And sometimes, this existential thirst cannot be quenched by anything external.

There is an old Jewish tale of an old man on a train who kept murmuring, “I’m thirsty… I’m thirsty…” A kind passenger brought him some water. The man drank it, then sighed, “How thirsty I was, how thirsty I was…”

This simple story shows that some forms of thirst reach beyond the body—they can only be soothed through being heard and understood. This is the essence of existential thirst.

Psychoanalytic Views on Existential Thirst

From a psychoanalytic point of view, the need for narrative has its roots in the earliest human experiences. Wilfred Bion, the British psychoanalyst, observed that even before the use of language or logical thought, people in small groups communicate through primitive emotional states—through feelings of emptiness, longing, or emotional thirst. When these needs are not met by a caregiver or the surrounding group, the person may remain trapped in persistent anxiety and pain. The old man on the train might well embody this state: his thirst was not just physical—it was existential, a longing to have his inner pain recognized. This is precisely the form existential thirst takes in human relationships.

Donald Winnicott, another psychoanalyst, described the concepts of the “true self” and the “false self.” For psychological growth to occur, the individual’s inner feelings and presence must meet with recognition and responsiveness from others. When someone shares their pain and another person listens with empathy, a circle of trust and validation is formed—helping the true self to consolidate. But when this circle of responsiveness is broken or weak, the person may withdraw into silence, or endlessly re-enact their pain through intrusive, repeating memories. Such conditions intensify existential thirst.

Storytelling as a Cure

Why, then, is storytelling so vital? The answer is simple yet profound: without narration, our experiences remain chaotic, fragmented, and devoid of meaning. Pain that cannot be spoken of lingers as an unprocessed emotional weight, sometimes surfacing as psychological or even physical symptoms. The act of storytelling transforms existential thirst into understanding.

Bion explained this through the idea of the mind’s “capacity to contain emotional experience”: to survive confusion and anxiety, one must be able to transform raw emotion into digestible, communicable form. Storytelling not only soothes the individual but also weaves the fabric of social and cultural connection. When stories are shared, people discover they are not alone—others, too, have faced suffering, failure, hope, and renewal. This shared recognition fosters empathy and strengthens our sense of belonging. Even when pain is deeply personal, narrating it can bring healing and self-acceptance. In this way, existential thirst finds its temporary relief.

The Languages of Expression and Existential Thirst

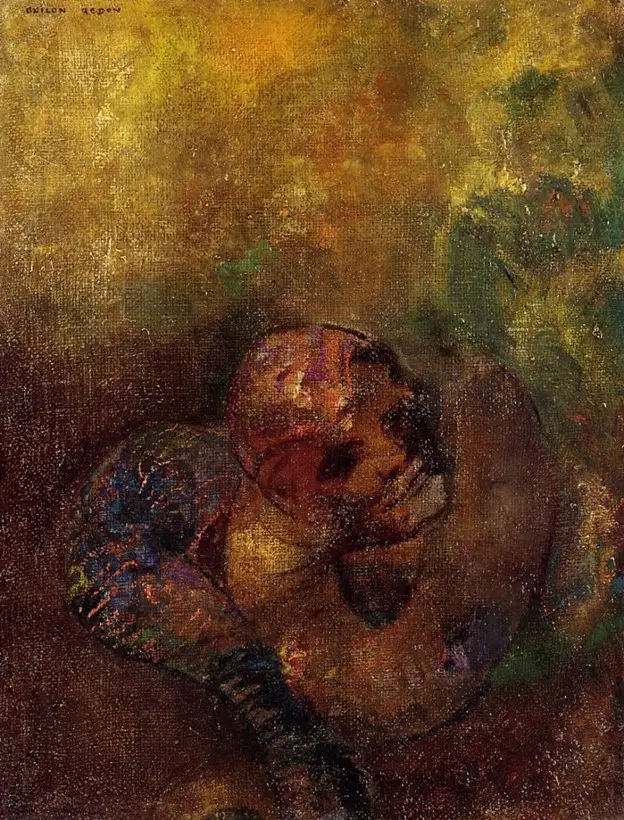

Importantly, storytelling does not always require words. Art, music, imagery, and movement can serve as languages of the body and soul. A child who cannot verbalize pain may express it through play or drawing. Adults, too, can quench their existential thirst through writing, poetry, or heartfelt conversation.

But when this possibility is denied, suffering does not fade—it returns, repetitive and wounding. Those who are never given space to tell their stories may become trapped in unprocessed emotion, anxiety, depression, or even bodily illness. Psychoanalysis teaches that dialogue itself is a form of healing—not because it provides immediate answers, but because it allows for recognition, acceptance, and the reconstruction of meaning. This process directly addresses the existential thirst at the heart of human life. [External Article]

Conclusion

In the end, the need for narrative is an inseparable part of being human—a thirst no material water can quench, but which is eased by being heard, understood, and transformed into story. Each of us, in some way, is that old man on the train whispering, “I’m thirsty…” The true response is not merely to offer water, but to listen—to accompany. That companionship lights the path through suffering and meaning, bridging the space between individual experience and our shared humanity.

Human beings are thirsty for stories, thirsty to be heard, and thirsty for meaning. Every tale, every exchange, every act of storytelling is a sip of water for the existential thirst that lives within us—a reminder that suffering is not just a burden but also an invitation to create meaning and connection. [Read More: Empathy and the unconscious: A critical review and summary]