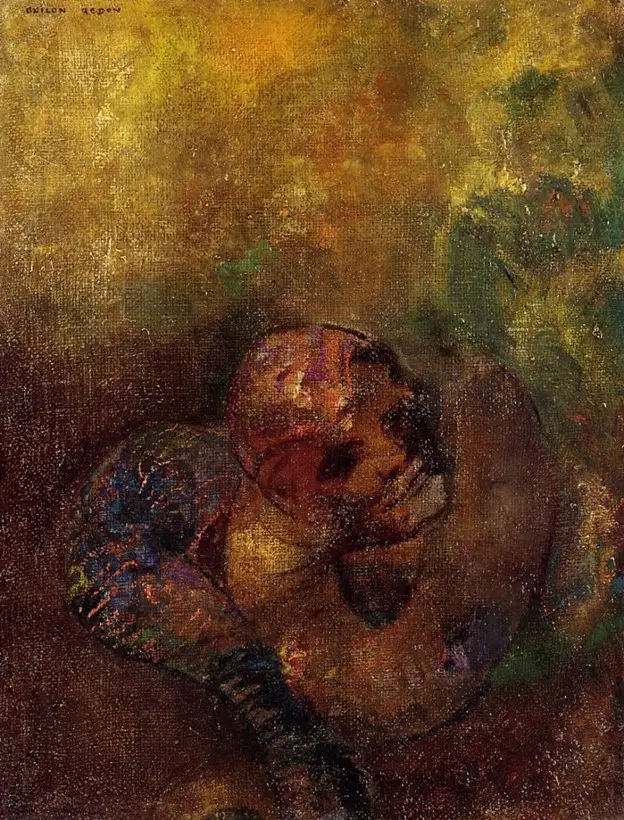

Fig. 1 — Frank Arnold (b. 1957), A Few More (2022). Oil on canvas [Image Reference]

“We do not remember the past; we live it in the present.”

— Philip Bromberg[1]

Author: Farhad Radfar

Audience: Psychotherapists, psychologists, mental–health students, and readers interested in trauma and dissociation

Reading time: ~4 minutes

A past that overwhelmed the child, a past carrying emotions far beyond their capacity—one lived at a moment when no regulating other was present to name it, soothe it, or give it meaning—never enters narrative memory. It neither disappears nor becomes truly remembered; instead, it remains half-alive in the hidden layers of the psyche. Bromberg calls this condition ghostliness, because an experience that could not be symbolized or narrated persists in the mind and body in a compressed, raw form. Years later it resurfaces in reactions that seem “unexplained”: sudden terror, panic attacks, bursts of rage, emotional freezing, fear of intimacy, or the familiar dissociative sense of “this is not- me”—as if the person slips outside themselves and watches from a distance. These sudden, nameless returns are ghostly precisely because they belong to the past yet live inside the present—a past that was never buried, never metabolized, never transformed into “the past,” and therefore continually occupies the now.

lived but unlanguaged past

In such a state, the person confronts a lived but unlanguaged past: an emotional memory that possesses neither the tools of language nor a temporal location. Dissociated experience has no clear place in the mind, so it settles in the body—in breath that tightens, in a throat that closes, in a sudden change of voice, in an instinctive withdrawal from touch, in eyes that avoid intimacy, or in silences that speak louder than words. What cannot be remembered is precisely what returns with instinctive, pre-verbal force at crucial moments of life. From an interpersonal psychoanalytic perspective, such returns occur when a hidden, dissociated self-state momentarily takes over, illuminates the stage of the mind for a brief second, and then slips back into darkness—leaving the person confused, unable to understand what has just occurred.

Yet this ghost can take on a face only in one specific space: relationship.

Bromberg explains that dissociated experience can emerge from its ghostly state only when it is summoned in the presence of a responsive, emotionally containing other—not through force or excavation, but through a process that unfolds between two minds and generates a new perceptual reality. The moment a patient realizes they can feel an emotion—one they have avoided for years—without collapsing; the moment they can endure a long silence in the therapist’s presence without shame or threat; or the moment they can speak, for the very first time, of an experience they always assumed was “insignificant”… that is the moment the ghost of the past gains a name, enters time, and shifts from half-life into a speakable experience. The therapeutic relationship—or any deep, responsive relationship—is therefore not merely a tool for change but a birthplace of narrative: a space where traumatic silences acquire language, and the body—after carrying the burden of the past for years—finally breathes a little more freely.

[1] Philip M. Bromberg (1931–2020) was an American psychoanalyst, a distinguished figure within the interpersonal psychoanalytic tradition, and one of the most influential contemporary theorists of dissociation. He is best known for his concept of self-states and his transformative claim that the mind is not a unified whole, but a shifting multiplicity of semi-independent, often unconscious selves. His books—most notably Standing in the Spaces and Awakening the Dreamer—have played a foundational role in shaping relational approaches, deepening our understanding of trauma, and guiding clinical work with dissociative experience.