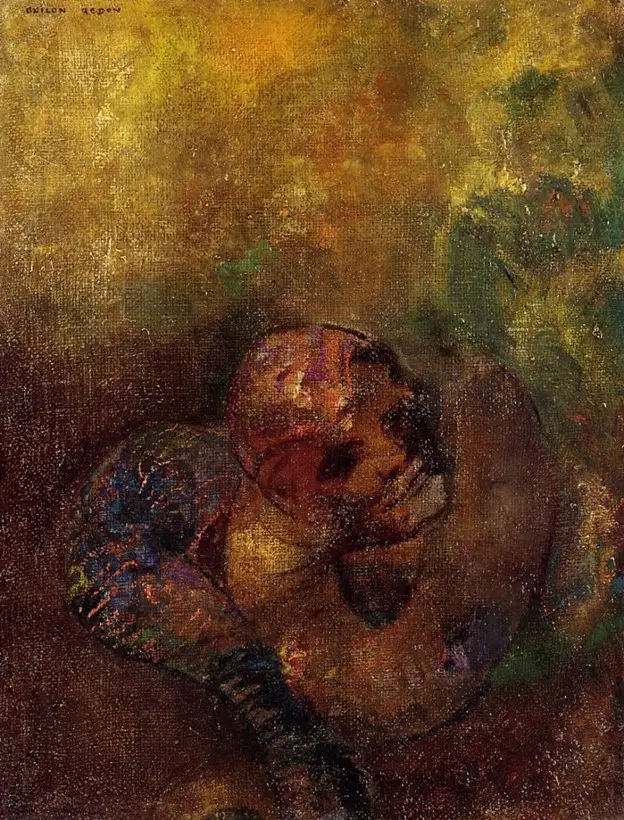

René Magritte, The False Mirror (1928), oil on canvas, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York [1] – Listening in Psychotherapy

Author: Farhad Radfar

Word Count: 803 words

Audience: Therapists and psychoanalysts

Reading Time: 4–5 minutes

The Illusion of Hearing

Listening in the consulting room is not always what it seems. A patient may speak, words may follow one another, a narrative may unfold, and yet the clinician senses that something is quietly disappearing beneath the surface of the voice. This subtle vanishing is the first sign—an indication that the capacity to listen is under strain. From that moment on, one must look more carefully at what is truly taking place in the room.

Fragmentation and Attacks on Linking

In one such session, “M.”, a woman in her early thirties who had grown up with a chronic sense of being misunderstood, created precisely this kind of atmosphere. From the moment she sat down, she launched into a series of narratives—stories filled with detail, sudden shifts of topic, and unfinished sentences. Each part of what she said felt like a piece of a puzzle that vanished as soon as it was placed. I was listening, yet I could feel the links between the pieces dissolving. It was exactly the phenomenon Bion described as “attacks on linking”: a state in which the patient, in order to protect herself, presents her experience as disconnected fragments so that no single piece becomes whole enough to overwhelm her.

Anxiety, Meaning, and the Breakdown of Listening in Psychotherapy

Gradually, a quiet pressure grew inside me—the need for clarity. The need for structure. This is usually the moment in which the clinician begins to impose premature meaning; a meaning that emerges not from capacity, but from defense. When I found myself saying, almost involuntarily, “Can you tell me which part felt hardest for you?”, it was not curiosity that spoke but anxiety—anxiety that wanted to gather the scattered pieces and force them together. Her response was immediate. She paused, lowered her gaze, and said softly, “I thought… you wouldn’t understand either.”

Absent Presence and the Failure of Listening in Psychotherapy

That sentence illuminated the entire underside of her narrative. Instead of entering the “outer meaning” of her story, I needed to enter her inner experience—the experience shaped over years with an Other who could not understand. André Green reminds us that meaning is sometimes absent not because it was never there, but because it has been actively deleted. “M.’s” narrative was just that: full of presence and simultaneously emptied of any meaning that could be held. Without intending to, I had stepped into the same relational circuit—an encounter with an Other who “hears but does not understand.” This is the “absent presence” Green so precisely articulates.

The Collapse of Listening in Psychotherapy When Knowledge Takes Over

When I felt the small silence that followed her response—the very silence Lacan called the place of “what is not said”—I understood that the problem was not the story, but the fear around which the story revolved. A fear at the core of her speech that had no name. A fear that if she said things directly, or laid her experience bare, she would return to the very place she had been so many times as a child: facing an Other who “has ears, but not for her.”

This is precisely the moment when, if the clinician stands in the position of “knowing,” listening collapses. Knowledge, even technical knowledge, becomes a shield—one that protects the clinician from the patient’s raw confusion but simultaneously cuts the thread of the relationship. I felt it: instead of being present, I had begun to think. And thinking, in such moments, is often the quickest escape from listening.

Restoring Listening in Psychotherapy: Staying With Not-Knowing

At that point, a small shift occurred within me—the shift Bion called “a return to a state without memory and without desire.” I took a breath and said, “I think something is getting lost between us. Not only for you—also for me. I’d like us to stay with this losing-our-way, without rushing to understand it.” In that sentence, something realigned. “M.” lifted her head, her eyes softened, and she said, “No one has ever said we can not understand something… and still go on.”

The Ethics of Listening in Psychotherapy

That sentence was the true moment of treatment—the moment of listening. Not listening to words, but listening to an experience that had not yet found language. An experience that would have been denied if given meaning too quickly, but came alive when held in ambiguity. It was here that Bion, Lacan, and Green converged: the capacity to tolerate ambiguity, the ability to hear absence, and the courage to stand in the space between two words.

Therapy, in such moments, is above all an ethical act. The ethics of presence. The ethics of staying with incompletion. The ethics of allowing something to find air before it finds meaning. Listening is precisely that: staying beside an experience not yet born, and bearing the discomfort of its namelessness. In this state, the clinician does not say, “Tell me so I can understand,” but instead, “Let us stay here until it becomes possible to speak.”

Listening in Psychotherapy as a Psychological State

Listening, then, is neither technique nor skill—it is a psychological state. A state that becomes available only when the clinician releases the urge to know and moves toward being. And it is exactly in that movement that the patient, slowly and carefully, steps out of the orbit of avoidance and enters a space where something can finally be heard. [Read More: Life in the Shadow of Loss]