Fig. 1— Edward Hopper, Morning Sun (1952) Oil on canvas, 101.9 × 71.5 cm, Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio. [Image Reference]

Five Scenes from a Human Experience, A psychoanalytic essay on mind, body, art, and lived experience

Author: Farhad Radfar

Audience: Readers interested in psychoanalysis, neuroscience, and art

Reading time: 8 minutes

1. Holding silence or shutting down? A silence that brings us back, or an absence that erases us.

Sometimes the mind grows tired—not of sound, but of perception itself. People come too close, emotions swell beyond what the mind can contain, and it becomes natural to withdraw and call that movement “silence.” But silence is never a single phenomenon. Some silences protect us.

Some silences shut us down. There is a silence that restores, and a silence that collapses us inward. The difference lies in the direction of the movement—and in its consequences. [ Read More: Existential Thirst: The Deep Longing to Tell Our Stories ]

2. Silence as container or collapse (Bion)

Bion argued that raw emotional experience cannot be processed directly. He called this raw, undigested material beta-elements—emotional content the mind cannot metabolize alone. “Raw emotion is like unprocessed food; it needs a container that can hold it, digest it, and return it in a tolerable form.” Sometimes this container is another person. And sometimes the container is silence itself: a silence that metabolizes affect, expands capacity, and allows the psyche to return to itself without fragmentation. This is containing silence. But when no container is available—no internal or external presence—the same silence collapses into shutdown. The link breaks, and what remains is not calmness but collapse.

3. Safe silence and shutdown (Neurobiology)

Neurobiology sharply distinguishes between these two states. When the ventral vagal system (the social engagement system) is active, the body signals safety: regulated breathing, open facial expression, connected gaze. The higher cortical networks remain online. This is holding silence—a biological invitation to return. But under extreme stress or relational threat, the dorsal vagal system dominates, pulling the organism into freeze, collapse, and disconnection.

This is shutdown, not silence. Shutdown is the body’s last defense—an old evolutionary reflex that cuts down energy, feeling, and relational availability.

4. Clinical and everyday signs: the return of desire, or its quiet death?

How can we distinguish healthy silence from shutdown? Sometimes the criterion is simple: If you emerge from silence with the desire to reconnect, reflect, or return, you were in holding silence. If desire disappears, you were in shutdown. Shutdown is often a childhood learning.

Some children grow up in homes where speaking, feeling, or even being is dangerous. Others grow up in families where the problem is not suppression but enmeshment—where the child becomes the emotional regulator of adults. Enmeshment teaches the child:

- If I pull away, someone collapses.

- If I assert myself, someone is hurt.

- If I choose myself, the entire system breaks.

Thus, the child learns to silence themselves—not for internal safety, but to preserve the emotional stability of others. Their silence is not holding; it is shutdown. Lacan famously said: “Man is what he desires.” But in enmeshed systems, desire becomes a threat: to feel it is disloyal, to express it is cruel, to pursue it is catastrophic. Thus, in order to survive the relational field, the child kills desire. And shutdown becomes the quiet death of longing. Holding silence restores desire. Shutdown extinguishes it.

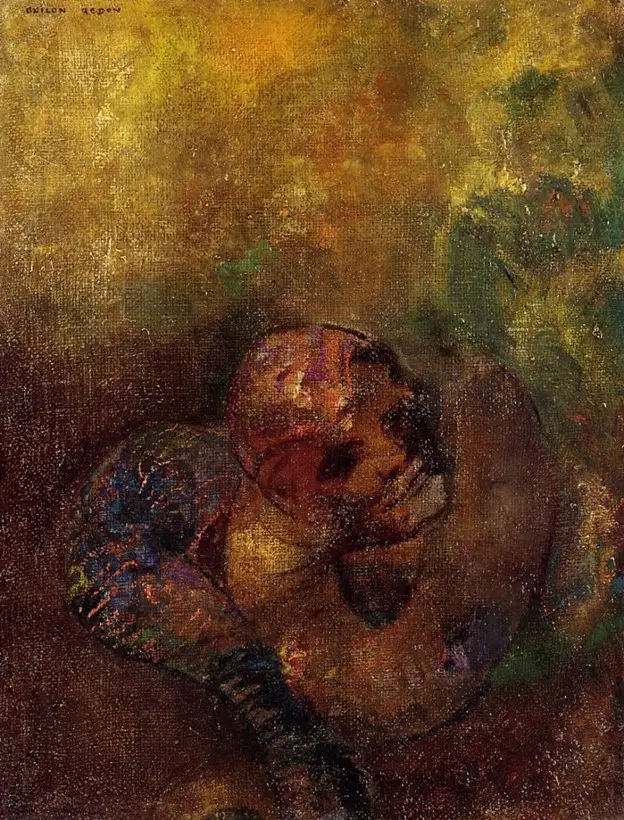

5. Silence reflected in art: Hopper and Morning Sun

Art often reveals psychological truths even before theory articulates them.

A woman sits on a bed, bathed in sunlight. [Download Original Image] Yet the light is not simply light. Critics observe:

“The light is the shape of her mind; the shadow on the bed is the shape of her body.” She sits in brightness, yet her interior world is dimmed. Hopper often portrayed individuals caught between presence and absence. In this painting, the woman’s thought—her inner emptiness—expands far beyond her body. She is physically present yet psychically withdrawn. Behind the aesthetics lies a painful biographical note: The model is Hopper’s wife, Jo—herself an artist who abandoned her own work to support his career, living within a relationship marked by control and emotional erasure. In the early sketches of the painting, her face is visible. In the final version, her face dissolves into anonymity. This is shutdown rendered visually. A body present, a psyche gone offline. In Bion’s terms, this is the moment when the link dies.

Conclusion

Silence is never one thing. Sometimes it holds us; sometimes it shuts us down.

Sometimes it restores desire; sometimes it erases it. What differentiates the two is not philosophy, but physiology—not the absence of sound, but the presence or absence of one’s self-state. If silence brings you back to yourself, it is holding silence. If silence drains your vitality, fragments your desire, or disconnects you from others, it is shutdown. Thus, the essential question becomes: When you become silent, do you return, or do you disappear? The body always knows the answer.